Drunken Angel

| Drunken Angel | |

|---|---|

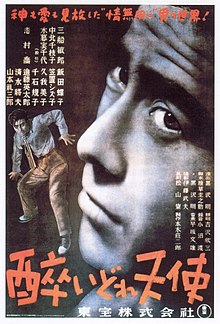

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Akira Kurosawa |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by | Sōjirō Motoki |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Takeo Itō |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Fumio Hayasaka |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Toho |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Drunken Angel (醉いどれ天使, Yoidore Tenshi) is a 1948 Japanese yakuza noir film directed and co-written by Akira Kurosawa. It is notable for being the first of sixteen film collaborations between director Kurosawa and actor Toshiro Mifune.

Plot

[edit]Sanada is an alcoholic doctor (the titular "drunken angel") in postwar Japan who treats a small-time yakuza named Matsunaga after a gunfight with a rival syndicate. The doctor, noticing that Matsunaga is coughing, diagnoses the young gangster with tuberculosis. After frequently pestering Matsunaga, who refuses to deal with his illness, about the need to start taking care of himself, the gangster finally agrees to quit boozing and womanizing and allow Sanada to advise care for him. The two enjoy an uneasy friendship until Matsunaga's fellow yakuza and sworn brother, Okada, who is also the abusive ex-boyfriend of the doctor's female assistant Miyo, is released from prison. In the meantime, Sanada continues treating his other patients, one of whom, a young female student, seems to be making progress against her tuberculosis.

Matsunaga quickly succumbs to peer pressure and stops following the doctor's advice, slipping back into old drinking habits and going to nightclubs with Okada and his fellow yakuza. Eventually, he collapses during a heated dice game after losing heavily, and is taken to Sanada's clinic for the evening. Okada shows up and threatens to kill the doctor if he does not tell him where to find Miyo, and while Matsunaga stands up for the doctor and gets Okada to leave, he realizes that his sworn brother cannot be trusted. Matsunaga then finds out that the boss of his syndicate, who gave him control of Okada's territory during his time in prison, intends to sacrifice him as a pawn in the war against the rival syndicate. Okada orders the storeowners in his territory to refuse service to Matsunaga as retaliation for challenging him.

Sanada goes to report Okada's harassment to the police, while Matsunaga discreetly leaves the clinic and goes to Okada's apartment. There, he finds the yakuza with Nanae, Matsunaga's former lover, who had abandoned him due to his failing health. He angrily tries to stab Okada, but starts to cough up blood; Okada then stabs him in the chest, and Matsunaga stumbles outside before he succumbs to his wounds and dies.

Okada is later arrested for the murder, but Matsunaga's boss refuses to pay for his funeral. A local barmaid, who had feelings for Matsunaga, pays for it instead and tells Sanada that she plans to take Matsunaga's ashes to be buried on her father's farm, where she had offered to live with him. The doctor retorts that while he understands how she feels, he cannot forgive Matsunaga for throwing his life away. Just then, his patient, the female student, arrives and reveals that her tuberculosis is cured and the doctor happily leads her to the market for a celebratory sweet.

Cast

[edit]

| Actor | Role |

|---|---|

| Takashi Shimura | Doctor Sanada |

| Toshiro Mifune | Matsunaga |

| Reisaburo Yamamoto | Okada |

| Michiyo Kogure | Nanae |

| Chieko Nakakita | Nurse Miyo |

| Eitarō Shindō | Takahama |

| Noriko Sengoku | Gin |

| Shizuko Kasagi | Singer |

| Masao Shimizu | Oyabun |

| Yoshiko Kuga | Schoolgirl |

Production

[edit]While looking for an actor to play Matsunaga, Kurosawa was told by one of the casting directors about Mifune, who was auditioning for another movie where he had to play an angry character. Kurosawa watched Mifune do this audition, and was so amazed by Mifune that he cast him as Matsunaga. On the film's Criterion Collection DVD, Japanese-film scholar Donald Richie comments that Kurosawa was impressed by the athletic agility and "cat-like" moves of Mifune, which also had bearing in his casting.

Censorship issues in Drunken Angel are covered extensively in a supplemental documentary by Danish film scholar Lars-Martin Sorensen, created for the Criterion Collection DVD release of the film, entitled Kurosawa and the Censors.[1] Produced and released during the American occupation in Japan, the Drunken Angel screenplay had to comply with a censorship board issued by the U.S. government. The board did not allow criticism of the occupation to be shown in Japanese films at that time.

Kurosawa slipped several references to the occupation, all of them negative, past the censors. The opening scene of the film features unlicensed prostitutes known as "pan pan" girls, who catered to American soldiers. The gangsters and their girlfriends all wear Westernized clothing and hairstyles. Kurosawa was not allowed to show a burned-out building in his black-market slum set,[2] but he did heavily feature the poisonous bog at the center of the district. English-language signage was also not allowed, but the markets on set have several examples of English usage on their signs. The dance scene in the nightclub features an original composition ("Jungle Boogie", sung by Shizuko Kasagi) with lyrics by Kurosawa, satirizing American jazz music; Kasagi imitates Johnny Weissmuller's famous yell from the Tarzan movies, and the way Kurosawa frames the singer parodies the American film noir movie Gilda.[3] The censorship board was unable to catch these subtle breaches due to overwork and understaffing, but censors did require Kurosawa to rewrite the film's original, more "gruesome" ending.[3][4]

The film was made in the context of a series of labor disputes with the Toho company. After the film's completion the strikes escalated and Kurosawa, disillusioned by studio executives' attitudes to the union, and the state of siege the occupying strikers were placed under by police and the American military, left Toho. In his memoir Kurosawa writes that the studio "I had thought was my home actually belonged to strangers".[5]

Music

[edit]Kurosawa used music to provide contrast with the content of a given scene. In particular was his use of The Cuckoo Waltz by J. E. Jonasson. During filming, Kurosawa's father died. While he was in a sad state, he heard The Cuckoo Waltz playing in the background, and the whimsical music made him even more depressed.

Kurosawa decided to use this same effect in the film, at the low point in the life of Matsunaga, when the character realizes that he was being used all along by the syndicate boss. Kurosawa had the sound crew find the exact recording of The Cuckoo Waltz that he had heard after his father died, and had them play the instrumental beginning of the song repeatedly for the scene in which Matsunaga walks down the street after leaving the boss.[3] In the opening scene for Okada, Kurosawa wanted him to perform on guitar "Mack the Knife". Originally "Die Moritat von Mackie Messer" which was a song composed by Kurt Weill with lyrics by Bertolt Brecht for their music drama Die Dreigroschenoper, but the studio could not afford the rights to the song.[6]

Themes

[edit]Stephen Prince in his analysis of Kurosawa's filmography considers the "double loss of identity" present within the film. One loss implying a reformation of social identity whereby the progressive individual should separate themselves from the family (embodied in the yakuza), and the other being symptomatic of a "national schizophrenia" that has resulted from the Americanization of Japan.[7] In the film the young are cut off from the past but still bound by its social mores. Prince writes that the narrative and spatial confinement of much of the film close to the sump returns the action to sickness, posing the question of how recovery can emerge from a humane ethic under post-war conditions.[8]

Release

[edit]Theatrical

[edit]Drunken Angel was released in Japanese cinemas on April 27 1948.

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Drunken Angel has a 93% approval rating.[9]

Writing in 1959 for the New York Times, Bosley Crowther cites the film's developing "brooding and brutish mood" and "poisonous atmosphere" in his positive appraisal of its symbolic moral conflict. He also gives a positive account of the acting and Kurosawa's "forceful imagery", despite criticizing some of the film's "derivative techniques" and clichés.[10]

Legacy

[edit]Drunken Angel is often considered Kurosawa's first major work. The director later reflected on the film's structural weakness which he mostly attributed to Mifune's intense screen-presence, one which overshadowed Shimura's role as the moral center of the film.[11]

In The Yakuza Movie Book: A Guide to Japanese Gangster Films (2003), Mark Schilling cited the film as the first to depict post-war yakuza, although he noted the movie tends to play off the yakuza film genre's common themes rather than depict them straightforwardly.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ The Criterion Collection | Drunken Angel by Akira Kurosawa | Special Features

- ^ From Sorensen's documentary, showing footage of censorship notes written on the Drunken Angel screenplay.

- ^ a b c From the documentary, Kurosawa: It Is Wonderful to Create, available on The Criterion Collection DVD.

- ^ Conrad, David A. (2022). Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan, pp59-61, McFarland & Co.

- ^ Kurosawa, Akira (1983). Something Like an Autobiography. Translated by Bock, Audie E. (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 166–168. ISBN 978-0-394-71439-4.

- ^ Harris, Michael (2013). "Jazzing in the Tokyo slum: music, influence, and censorship in Akira Kurosawa's Drunken Angel". Cinema Journal. 53 (1): 61. doi:10.1353/cj.2013.0067. S2CID 193175605.

- ^ Prince, Stephen (1991). The Warrior's Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa (Revised and Expanded ed.). Princeton University Press (published 1999). p. 86.

- ^ Prince, Stephen (1991). The Warrior's Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa (Rev. and expanded ed., [Nachdr.] ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (published 1999). p. 89. ISBN 978-0-691-01046-5.

- ^ Drunken Angel (1948), retrieved 2019-07-03

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (1959-12-31). "The Screen: Japanese 'Drunken Angel'; Kurosawa Drama at Little Carnegie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 October 2023. Retrieved 2024-08-21.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Prince, Stephen (1991). The Warrior's Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa (Revised and expanded ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (published 1999). p. 88. ISBN 978-0-691-01046-5.

- ^ Schilling, Mark (2003). The Yakuza Movie Book : A Guide to Japanese Gangster Films. Stone Bridge Press. p. 314. ISBN 1-880656-76-0.

Bibliography

[edit]- Conrad, David A. (2022). Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan.

- Prince, Stephen (1991). The Warrior's Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa (Revised and Expanded ed.). Princeton University Press (published 1999). ISBN 978-0-691-01046-5.

External links

[edit]Movie sources

[edit]- Drunken Angel - Japanese With English Subtitles, online video (1 hour, 38 minutes, 14 seconds), at Archive.org

Reviews

[edit]- Drunken Angel at IMDb

- Drunken Angel at AllMovie

- Drunken Angel at the Japanese Movie Database (in Japanese)

- DVD Review: BFI - Region 2 - PAL

- Essay by Jay Carr at Turner Classic Movies

Commentary

[edit]- Drunken Angel: The Spoils of War an essay by Ian Buruma at the Criterion Collection

- 1948 films

- 1948 drama films

- Japanese drama films

- 1940s Japanese-language films

- Japanese black-and-white films

- Yakuza films

- Medical-themed films

- Best Film Kinema Junpo Award winners

- Toho films

- Films directed by Akira Kurosawa

- Films produced by Sōjirō Motoki

- Films with screenplays by Akira Kurosawa

- Films scored by Fumio Hayasaka

- Films about alcoholism

- Films about physicians

- Films about tuberculosis

- Japanese crime drama films

- Japanese psychological drama films